Jerusalem’s dwindling Christians celebrate the Holy Fire on Orthodox Easter

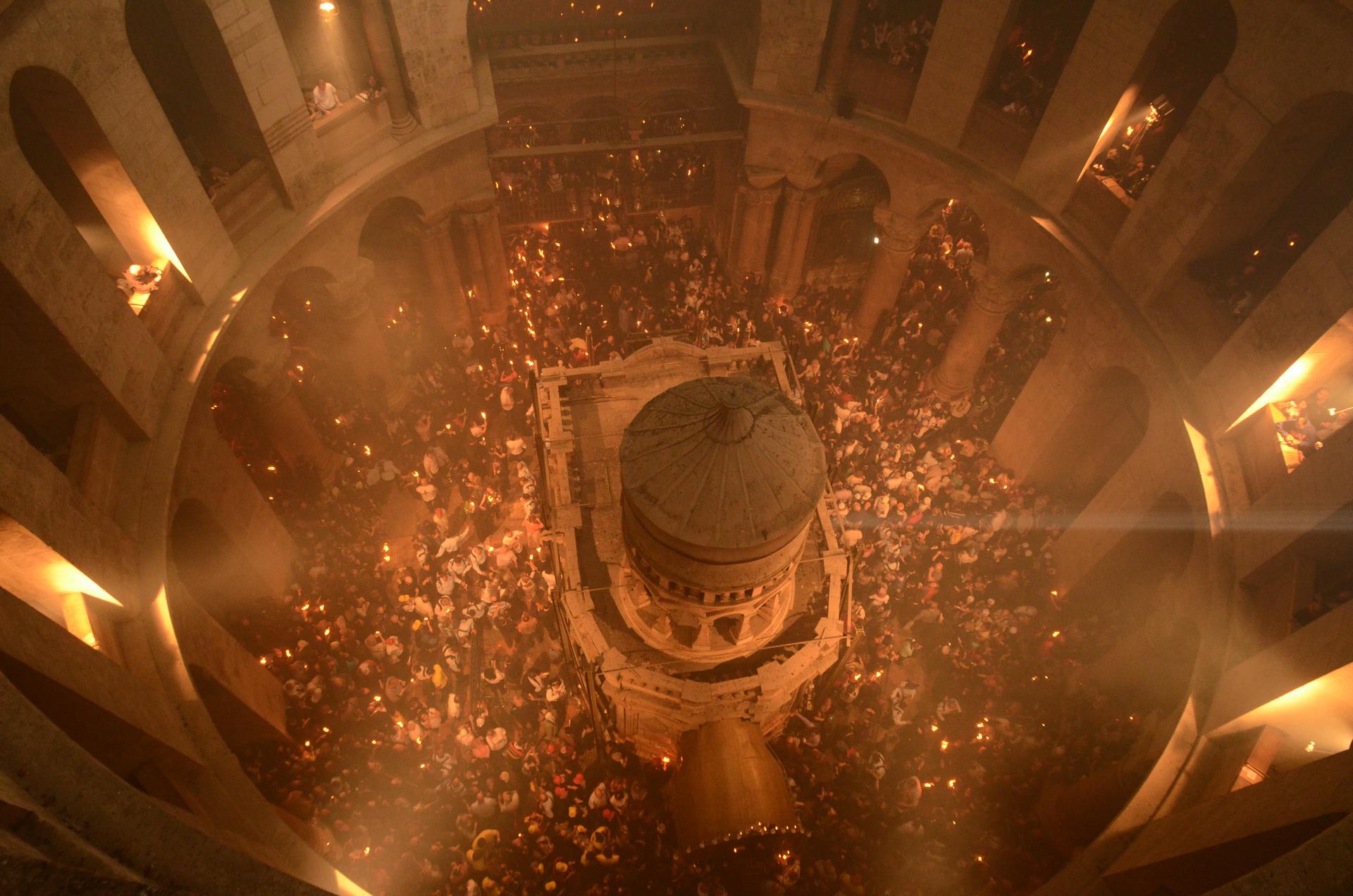

Christian faithful celebrate the Holy Fire, which believers see as an annual miracle that lies at the center piece of Orthodox Easter, at the Church of the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem.

This is the sixth in a series of posts about dwindling Christian communities in the Middle East.

JERUSALEM — A procession of Armenian Orthodox Christians wound from their quarter of Jerusalem’s Old City to the barred gate of the Church of the Holy Sepulcher.

The priest at their head carried an eight-inch, dart-like key that opens the doors to the 1500-year-old basilica. Thousands of Christians in Jerusalem and millions watching the live broadcast around the world waited for his arrival so that the Holy Fire, which believers see as an annual miracle that lies at the center piece of Orthodox Easter, could get under way.

An Israeli policeman stepped from the ranks of officers guarding the plaza. “What tour group are you from?”

Astonished, the priest looked out from under his pointed cowl, saying, “I’m here to open the church. These people aren’t tourists. They’re from here, from Jerusalem.”

The cop checked with his superior and ushered the priest through. When the aging locks were opened and the doors of the church thrown back, a phalanx of gray-clad men waited inside. They weren’t priests. They were from an Israeli riot control unit. A police presence brought on by some rowdy nights of celebrating the Holy Fire in the past which turned violent. But as the Christian presence here dwindles, the number of police seem to almost rival the number of local Christians.

| |

“In a couple of years there will only be police to light the candle from the Holy Fire anyway,” said George Dahoud, a Greek Orthodox Christian from Beit Hanina in northern Jerusalem.

Dahoud’s joke reflects one of the major fears of local Christians. Among the throngs of pilgrims from Russia and Georgia, Bulgaria and Macedonia, the local faithful were thinner in number than in decades past. The Christians of the Holy Land find themselves caught in other peoples’ conflicts. They are victims of the dispute between Israel and the Palestinian Muslim majority.

Around the region, they have been casualties of the Arab Spring in Egypt, suffered from the growing power of Hezbollah in Lebanon, and been forced to flee war in Iraq and Syria’s social meltdown. Fearing what their fate might be if an Islamist opposition came to power in Syria, many Syrian Christians – from the Eastern Orthodox rite the Roman Catholic church – have thrown their lot in with President Bashar al-Assad.

When youths from the Syrian Catholic denomination entered the Holy Sepulcher, they set up a chant. Even on this most holy of weekends there was to be no escape from the regional conflicts that have done so much to convince tens of thousands of Christians to emigrate.

“God, Syria, and only Bashar,” they chanted, in support of Syrian President Assad.

Above the entrance to the tomb where Christians believe Christ was buried and rose again, there’s an old oil painting of the Crucifixion. The image is faded almost beyond recognition, buried under a century of candle smoke. The Christians of the Holy Land are fading out just as surely.

"The Holy Fire gives us confidence as Christians," said Maha Nacacche, a middle-aged woman from Nazareth in northern Israel. "But it's hard to feel confident every day. As Christians in the Holy Land, we feel that our people are struggling to survive."

The Christian community in the Holy Land has been in decline for decades. But present numbers are shocking. Jerusalem’s 10,000 Christians represent only 2 percent of the city’s population, compared to 19 percent six decades ago. If the Christian population had grown at the same pace as its Jewish and Muslim neighbors, they’d be 100,000-strong now, according to an estimate by the Latin Patriarchate. Formerly Christian towns like Ramallah and Bethlehem boast considerable Muslim majorities too.

With relatively few Christians left, any emigrations are felt more deeply. During the Palestinian intifada of 2000-2005, Muslim gunmen in Bethlehem ran protection rackets to extract cash from Christian businessmen. Christians left en masse and few have returned.

In Gaza, the rule of Hamas Islamists has cut the Christian population by almost two-thirds to little over a thousand.

Some Christian leaders are trying to stem the tide.

Monsignor William Shomali, the Roman Catholic Auxiliary Bishop of Jerusalem, completed a nine-year construction project in Bethlehem last month that aims to provide housing for 80 Christian families. With Palestinians crowded into their towns by Israeli land policy in the West Bank, property is increasingly too expensive for young Christians. Shomali hopes his apartments will provide an alternative to emigration.

“The most we can do is to give Christians incentives. Not only material but moral incentives,” he says. “This is the Holy Land. Being born here, living here, even dying here is a blessing, a privilege and a vocation. The Lord wants you to be here.”

Last week, Israeli President Shimon Peres invited Pope Francis to be where the Lord wants him to be. The pontiff agreed to visit the Holy Land, though no date was set.

Francis’ flock here will be happy to have another papal visit to remind Christians around the world of their plight. During his 2009 visit, Pope Benedict XVI called the Holy Land a “fifth gospel, because here we see —indeed touch — the reality of the history that God realized together with men.”

The life the local communities inject into the historic traditions of the church is felt keenly at the Holy Fire ceremony.

Most of the pilgrims to enter the church in the early morning were outsiders with broad Slavic faces. They stood morosely waiting for the Holy Fire.

Later a group of local Greek Orthodox youths danced through the packed church thumping out rhythms on their darbouka drums. The women ululated and the men chanted like sports fans: “Jesus, Jesus, savior.” The excitement in the church ticked up each time a pack of sweating Palestinian Christians processed around the tomb.

At 1:30 p.m. a Greek Orthodox priest brought an ornate silver urn inlaid with gold and jewels and set it inside the sepulcher. The “miracle” of the Holy Fire is the kindling of a fire inside the urn from a pillar of light that descends to Jesus’ tomb. Skeptics believe the urn contains white phosphorous which spontaneously combusts about a half hour after it’s left to dry.

Conveniently, a half hour later, the Greek Orthodox leader Theophilos III walked five times around the tomb in clothing no less ornate than the urn that would contain the Holy Fire. Then he entered the tomb with Armenian Patriarch Nourhan Manougian.

A few minutes later flat-tuned Orthodox bells rang out and Theophilos emerged from the tomb stripped of his finery. Now he was a wild-haired old man with a long, white beard swept up by the miracle.

He waved two bundles of foot-long candles, lighting the tapers of the pilgrims and priests around him. Two acolytes caught him under his arms and raced him through the church as if it were he who had combusted.

The Armenian Patriarch was scarcely less transformed. He paraded out of the church on the shoulders of two young priests, waving his bundles of candles.

Within moments, the air in the rotunda filled with the incense embedded in the big wax faggots. The thousands of kindlings sent the temperature to sauna levels. Pilgrims wielded the flames casually, seeming to believe in the notion that the Holy Fire does not burn.

The energy that filled the church was such that anyone there would surely have wished for the miracle to be real. Just as surely, they’d have longed for an even greater miracle to save the Christian presence in the Holy Land.

Read parts one, two, three, four and five of this series, about dwindling Christian communities in the Middle East.