Two court cases take diverging path when it comes to digital rights

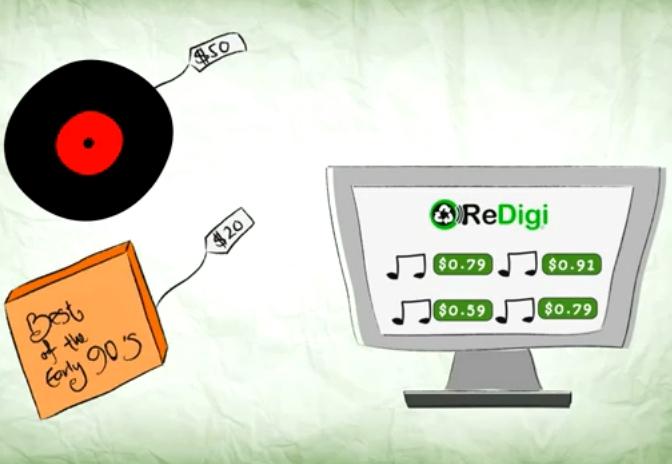

ReDigi sought to help people sell off the old MP3s that they purchased but no longer are interested in owning.

Two different federal courts this week delivered important and seemingly contradictory decisions about the way we consume digital entertainment.

One case involves ReDigi, a platform that lets you resell digital songs you bought from iTunes but decide you don’t want on your computer any more — like taking your CDs to the secondhand store. Record companies argued that because the technology requires that a copy be made, ReDigi’s service infringes on their copyrights. U.S. District Court Judge Richard Sullivan agreed.

The other case involves a new digital streaming service called Aereo, which captures broadcast TV signals and routes them over the Internet to users who pay a fee. Network broadcasters took Aereo to court, but in Judges Christopher Droney and John Gleeson from the U.S. Second Circuit Court of Appeals refused to issue an injunction against Aereo.

TV viewers 1, iTunes users 0.

Both cases “turn on the idea of what’s unique and what’s one-at-a-time,” according to Adam Liptak, who covers law and the Supreme Court for the New York Times. Although ReDigi’s model promises to move our unwanted MP3s to a secure digital locker where they become inaccessible to the seller, the service is “too clever by half,” Liptak said.

“There are problems every step of the way as a matter of law and as a matter of technology,” he said The 1976 Copyright Act “treats these (audio files) as reproductions, as copies, not as a single unitary material object that you’re moving from place to place.”

In the case of Aereo, earlier decisions that allow us to use DVRs and VCRs set a key precedent, though.

Aereo uses thousands of antennas, each assigned to an individual subscriber, to pull down broadcast TV waves.

“Here the court was persuaded that the individual antenna makes it enough of a one-at-a-time thing,” Liptak said.

The fact that these cases are decided based on a law that predates the digital era by decades makes a lot of work for lawyers and judges. It’s up to Congress do the real heavy lifting of changing the laws for the digital era.

“The Copyright Act needs to take account of where we are now and not in 1976,” said Liptak, who doubts that will come to pass. “The correct answer is that it should be Congress, and the likely real-world answer is it’ll be the courts” that continue ruling on digital rights.