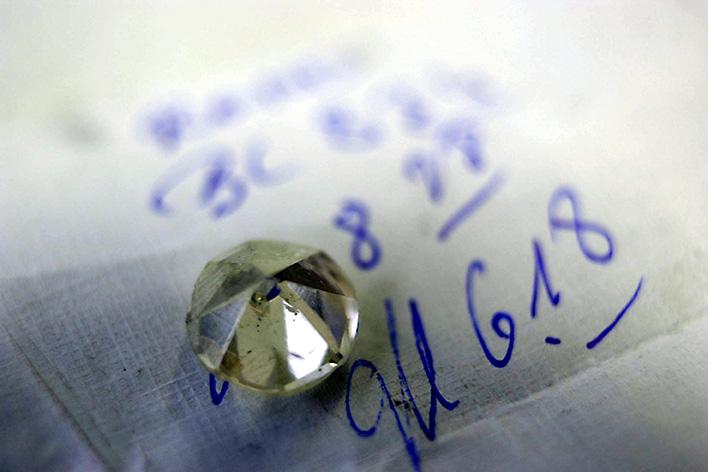

Still for sale in Belgium

A diamond sits on its polishing instructions in Antwerp, Belgium, Oct. 31, 2002.

Editor's note: You’ve probably seen the movie. “Blood Diamond” — starring Leonardo DiCaprio and his down-home Rhodesian accent — that delves into the dusty, deadly world of mining diamonds to finance conflicts in African war zones.

The film didn’t paint a pretty picture. But it did intensify the spotlight on the issue, which itself was reflective of real-world events like the Kimberley Process in 2000 — which drew governments and industry together in an effort to stem the deadly trade.

But here we are a decade later and the buzz has died down. There is still talk about blood diamonds, but the multi-billion dollar global trade has hardly come to a grinding halt.

GlobalPost takes a look at how the ongoing ugliness ties the world together — from the raw diamond mines in Zimbabwe to India, where little-known middlemen polish the stones ‘til they shine on the shelf in Antwerp, hidden from view unless you know who to ask.

As long as diamonds are forever, blood diamonds will be too.

ANTWERP, Belgium — The narrow walkway between rows of drab 1980s buildings just west of Antwerp’s ornate Central Station is the unlikely hub of a glamorous global trade worth around $60 billion a year.

Behind the glass and concrete facades of Hoveniersstraat around 80 percent of the world’s rough diamonds are traded, along with 50 percent of the polished stones.

Last year, the Antwerp World Diamond Center recorded turnover of $41.9 billion, bouncing back from the slump in 2009.

But there is a shadow hanging over this glittering trade, one that risks recalling the dark days of the 1990s when the industry’s reputation was tarnished by sales of “conflict diamonds” that financed bloody African civil wars.

Read more: Many African diamonds still bloody

In response to that scandal, the industry adopted the set of rules known as the Kimberley Process designed to track the origins of gemstones and make sure “blood diamonds” don’t reach the market.

However the growing realization that the Marange diamond fields in eastern Zimbabwe are among the richest in the world is testing the system to breaking point as traders compete for a share of this vast treasure trove despite of reports murder, torture and forced labor in the mining area and concerns that diamond riches are funding President Robert Mugabe’s crackdown on the opposition.

“There are some industry predictions that say that the diamonds in the Marange diamond fields, if fully and properly exploited, could account for 30 to 40 percent of total rough diamond supply, so the industry is desperate to get their hands on it regardless of what was happening in Zimbabwe,” says Annie Dunnebacke, senior campaigner at Global Witness, the campaign group which helped expose the blood diamond scandal in the 1990s.

Global Witness led a walk-out by civil society groups from a key meeting of the Kimberley Process in June when the chairman overruled objections of the United States and European Union to allow Zimbabwe’s diamonds back onto world markets.

More: Zimbabwe selling blood diamonds

The campaign groups plan to boycott another key meeting in November in protest over the Zimbabwe situation and have threatened to withdraw from the Kimberley Process altogether, a move that could undermine the whole system for verifying diamonds.

Antwerp has been supportive of the Kimberley Process as helping restore the industry’s good name after consumers were scared away in the 1990s by revelations of how diamonds funded brutal conflicts in Angola, Sierra Leone and Liberia.

“Thanks of the process it was possible for the first time to create a map of the entire industry,” said Caroline De Wolf, communications manager of the Antwerp World Diamond Center. “That was an incredible step forward because it made it possible to create a regulatory framework for the production and trade of rough diamonds. From that day on control was possible.”

De Wolf insisted that Antwerp applies the Kimberley rules strictly even at the cost of losing business to other trading centers where controls are more lax.

“Antwerp sets the example for many diamond centres … upholding the highest standards globally for the Kimberly Process for diamonds through its Diamond Customs Office. We do however feel that it often weakens our competitive position, and that is a problem. It’s necessary that there is a playing field at the highest possible level,” she told Globalpost.

Campaigners acknowledge that Antwerp has tighter technical controls in place than some emerging trading centers such as Dubai or Surat in India, which is the world’s center for cutting and polishing diamonds.

However, Dunnebacke says investigations by Global Witness suggest that Antwerp has been a major transit point for conflict diamonds from Ivory Coast, in contravention of Kimberley process rules and she says the Belgian government has acted as a brake on the European Union taking a tougher line on Zimbabwean diamond exports.

More: Naomi Campbell to testify over blood diamonds

Antwerp’s role in the world diamond trade is crucial to the Belgian economy, accounting for 5 percent of the country’s total exports.

The history of diamond trading in Antwerp dates back 500 years, but the city cemented its role as the leading world diamond hub in the late 19th century when a combination of lower wages and looser regulations allowed it to eclipse its main rival Amsterdam.

Trading is concentrated in a square mile squeezed between the railroad tracks and the city part. The diamond district is ringed by streets filled with small retail jewellery stores, but as you penetrate deeper into the neighborhood it becomes clear that something more significant that $1,000 replicas of Kate and Williams’ engagement ring are being traded in the district’s heart.

Security is tight around the discreet entrances to the diamond exchanges along Hoveniersstraat and not just because of the billions of dollars worth of gem stones changing hands. This month, the district is comemorating the 30th anniversary of a truck bomb attack on the Hoveniersstraat synagogue which killed three people.

Jews have traditionally played a leading role in the Antwerp diamond trade, but in recent years, traders from India, Russia, Lebanon and other areas have moved in. Today, Indians in beige slacks and open-necked shirts mingle with Hassidic Jews in broad-brimmed hats and long black coats outside café’s serving up pastrami sandwiches or plates of falafel.

Out on the street, there’s a constant babble of Hebrew, Levantine French, Chinese, Flemish or the English in accents from London, Bombay, Johannesburg or Brooklyn as traders bellow down cell phones. The diamond district is home to 160 nationalities.

Antwerp is confident of a bright future for the gem trade, spurred by demand in emerging economic powers.

“The spectacular growth of the middle class in a large number of countries, which just 10 years ago were considered to have developing or emerging economies, has meant that the market for diamond jewellery is growing by leaps and bounds,” says De Wolf. “The most prominent of these are China and India, but they are being joined by a good many others, including Brazil, Russia, South Africa, Indonesia and others.”

Zimbabwe’s enormous reserves would help meet that growing demand, but the cost could be high for the industry’s reputation.

“Zimbabwe is a bomb waiting to explode,’’ Dunnebacke warned. “The industry has to take more responsibility for what they are buying and whether it's caused any.If we want to have a truly clean diamond trade, then those things must change.”