Soldiers Protecting Art, Art Protecting Soldiers

Robert Edsel — founder of the arts preservation organization the Monuments Men Foundation — was deep in the Metropolitan Museum of Art archive vault when he found something extraordinary. It wasn’t a rare gem or a missing scroll, but an audio recording of a speech given by then-General Dwight D. Eisenhower at the museum on April 2, 1946.

The recording, recently released to the public, speaks to the importance of art and its protection during war. And at a time when conflicts (new and ongoing) rage in the Middle East, an area rich in cultural treasures, it’s a message that feels especially important.

Listen to a segment of the recording above.

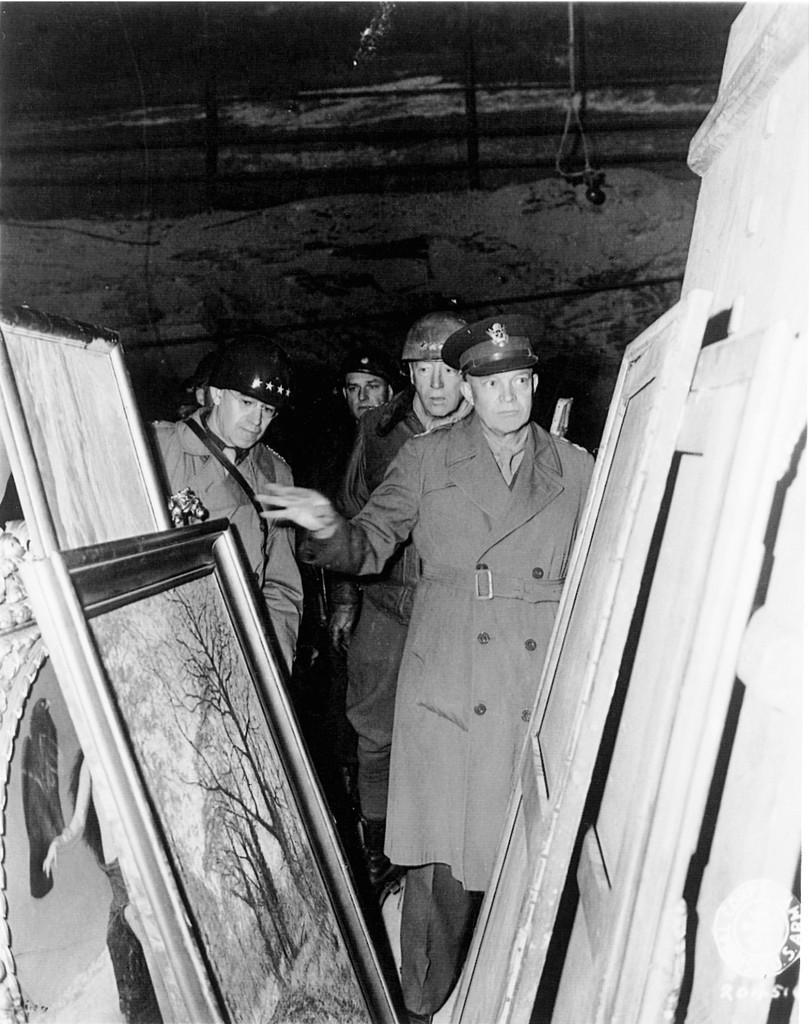

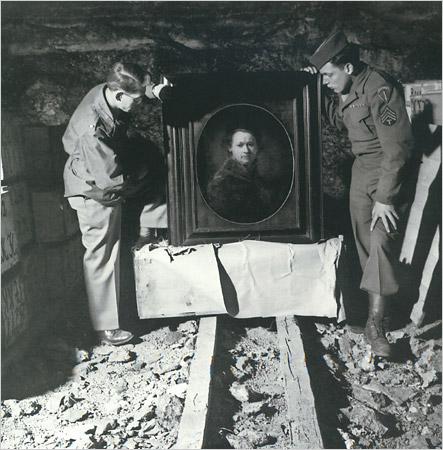

Throughout WWII, Eisenhower was explicit in his orders to soldiers: whenever possible, they were to protect and preserve pieces of art they came across — even if the pieces were discovered in the middle of battle. And to the credit of many soldiers, they were able to both experience and protect iconic works of art, including this self-portrait by Rembrandt.

In this photo, Lt. Dale V. Ford (left) and Sgt. Ettlinger (right) inspect the portrait, which was stored in a German salt mine. The salt actually helped to preserve this and other paintings by capturing moisture in the air.

For his efforts, Eisenhower was presented with an Honorary Life Fellowship from the Metropolitan Museum of Art. During his acceptance speech, he acknowledged the odd pairing of soldiers and art: “It may seem strange that a soldier, representative of the science of destruction, should appear before a body dedicated to the preservation of man’s creative ideals as expressed in art.” But it’s clear that his goals were in line with those of the Museum: “The freedom enjoyed by this country from the desolation that has swept over so many others during the past years gives to America greater opportunity than ever before to become the greatest of the world’s repositories of art.”

During the war, another group of about 345 men and women from 13 nations called the Monuments Men worked to track and recover art and cultural items taken by Hitler and the Nazis. They ultimately returned more than 5 million pieces, including Leonardo da Vinci’s “Lady with an Ermine.”

During the war, another group of about 345 men and women from 13 nations called the Monuments Men worked to track and recover art and cultural items taken by Hitler and the Nazis. They ultimately returned more than 5 million pieces, including Leonardo da Vinci’s “Lady with an Ermine.”

The Monuments Men served under the guidance of the Civil Affairs and Military Government Sections of the Allied Armies. Many were connected to the arts in some way — curators, art historians, museum directors. Some even remained in Europe after the war was over to continue to look for stolen pieces.

As Eisenhower explained to his audience at the Met, the artwork had special meaning for those who protected and recovered it:

“In no walk of life can man fail to find richer experience as he falls under the influence of beauty immortalized by inspired genius. Even for the roughest of soldiers there is more of ancient history to be felt and understood in a lonely, graceful column rising against the sky in a naked field than there is in all the descriptive matter that has ever been written on the subject. … They who have dwelt with death will be among the most ardent worshipers of life and beauty and of the peace in which these can thrive.”

Unfortunately, that message appears to be, itself, a museum piece. The order for “every commander to protect and respect these symbols whenever possible” expired with the end of the war and no similar order has been issued since. This troubles Robert Edsel, and not just because of the work lost when Iraq’s National Museum Art was looted in 2003. As monuments, libraries, and works of art are destroyed, he says the United States loses the war for the hearts and minds of the world. “That’s my great fear — we have got to learn to care,” he says, “because that’s the currency of the world… Why in the heck aren’t we doing it now when we did it so well during World War II?”